Review of “Literary Theory for Robots”: AI’s deep roots explored

4 min read

An undisclosed history of machine intelligence, from 14th-century horoscopes to 1930s ‘plot genies’ for creating storylines

Behold! The end approaches. “In the industrial age, automation affected the shoemaker and the factory-line worker,” Dennis Yi Tenen writes at the outset of “Literary Theory for Robots.” “Today, it affects the writer, the professor, the physician, the programmer, and the attorney.” Reminiscent of the doomsday movies that flooded theaters around the year 2000, newspapers and bookstores are now filled with economists, futurists, and social semioticians discussing artificial intelligence. Even Henry Kissinger, in “The Age of AI” (2021), discussed “epoch-making transformations” and an imminent “revolution in human affairs.”

Tenen, a tenured professor of English at Columbia University in New York, is not as pessimistic as he initially appears. His book has an intriguing title—do robots need literary theory? Are we the robots?—and differs significantly from the techno-theory of authors like Friedrich Kittler, Donna Haraway, and N. Katherine Hayles. Primarily, it advocates for reducing rhetorical tension. Tenen suggests that machines and literature have a long history together. His aim is to reconstruct “the modern chatbot from parts found on the workbench of history,” using “anecdotal strings and light philosophical commentary.”

The history of chatbots traces back to the 1377 Muqaddimah by the Arab philosopher Ibn Khaldun, which mentions “zairajah,” a form of “letter magic” involving a type of horoscope. This method used a large circle enclosing other circles representing various elements and branches of science. Was this an early form of analogical reasoning or astrological projection? Tenen describes its “computational” cycles and “procedurally generated text,” likening it to a “14th-century AI performance.” He suggests that the electronic databases in hospitals could be thought of as giant zairajah circles, weaving a narrative that connects patients, physicians, pharmacies, and insurance companies.

Tenen admires “lovely weirdos” like the 13th-century Mallorcan philosopher Ramon Llull, who influenced Francis Bacon

Tenen appreciates what he terms “lovely weirdos,” including historical figures like the 13th-century Mallorcan hermit and philosopher Ramon Llull. Llull’s rotating paper charts influenced both Francis Bacon and Gottfried Leibniz in their exploration of binary code and cipher systems. Another example is Georges Polti, a Frenchman whose “Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations” (1895) provided vivid scenarios (“daring enterprise,” “fatal imprudence,” “conflict with a god”) to writers lacking inspiration. Additionally, Andrey Markov, a Russian mathematician, developed models of probability—later known as the Markov chain—largely inspired by his study of linguistic patterns in Alexander Pushkin’s verse-novel “Eugene Onegin.” While these figures achieved remarkable feats, the label “weirdo” lacks biographical justification.

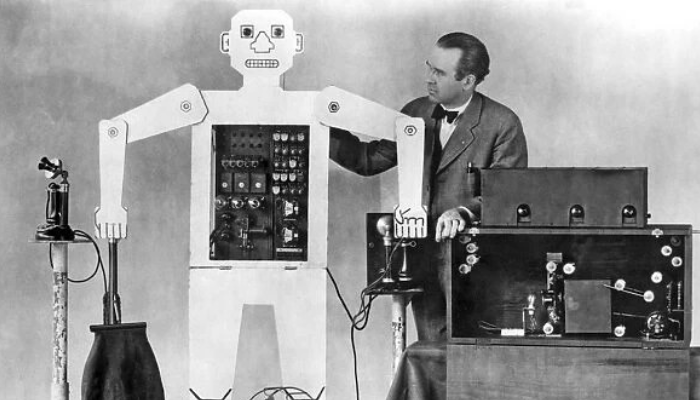

Tenen is more comfortable discussing technology than individuals. For example, he mentions a 1935 writing manual called The Plot Genie Index, which included a wheel known as the “Plot Robot” to assist users in creating stories. He also discusses how the Qwerty keyboard was designed to slow down typing and reduce the likelihood of keys jamming. In addition, as early as 1959, Bell Telephone Labs patented a device for the Automated Reading of Cursive Scripts. Furthermore, innovations like the Random English Sentence Generator received significant funding from the US army and air force. Boeing even utilized Vladimir Propp’s 1928 Morphology of the Folktale to improve its ability to generate useful reports about unusual aircraft events.

“Literary Theory for Robots” is part of a new series by Norton, where academics are tasked with condensing complex ideas into concise volumes for non-specialist readers. This poses a challenge as professors typically establish their reputation by writing for their peers rather than a broader public audience. Tenen attempts to adopt a lively and accessible tone but, akin to a TED Talk “thought leader,” his approach sometimes comes across as overly eager to please. For instance, one chapter begins with “Let me let you in on a little secret,” while another is titled “9 Big Ideas for an Effective Conclusion.” His writing is characterized by exclamation marks and awkward phrases (“Whoa, these things are old!”). Furthermore, the text contains unsubstantiated claims, such as the assertion that “modern humans” regard toasters “with disdain.” According to Tenen, not long ago, appearing smart involved memorizing obscure facts, but today, most people still value individual human genius over mechanical reproduction, revealing a lingering Romantic sentiment.

“Literary Theory for Robots” is part of a new series by Norton, where academics are tasked with condensing complex ideas into concise volumes for non-specialist readers. This poses a challenge as professors typically establish their reputation by writing for their peers rather than a broader public audience. Tenen attempts to adopt a lively and accessible tone but, akin to a TED Talk “thought leader,” his approach sometimes comes across as overly eager to please. For instance, one chapter begins with “Let me let you in on a little secret,” while another is titled “9 Big Ideas for an Effective Conclusion.” His writing is characterized by exclamation marks and awkward phrases (“Whoa, these things are old!”). Furthermore, the text contains unsubstantiated claims, such as the assertion that “modern humans” regard toasters “with disdain.” According to Tenen, not long ago, appearing smart involved memorizing obscure facts, but today, most people still value individual human genius over mechanical reproduction, revealing a lingering Romantic sentiment.

Tenen doesn’t discuss the death of the author, but he does mention his own perception of a “diminishing share of authorial agency.” By this, he means that when he uses dictionaries, encyclopedias, and search engines, he is relying on “a shadow team of scholars and engineers” who created those tools. To him, this realization is profound: “Intellect necessitates artifice, and thus labor.” However, I am not aware of anyone, whether a book historian or a general reader, who has ever believed otherwise.