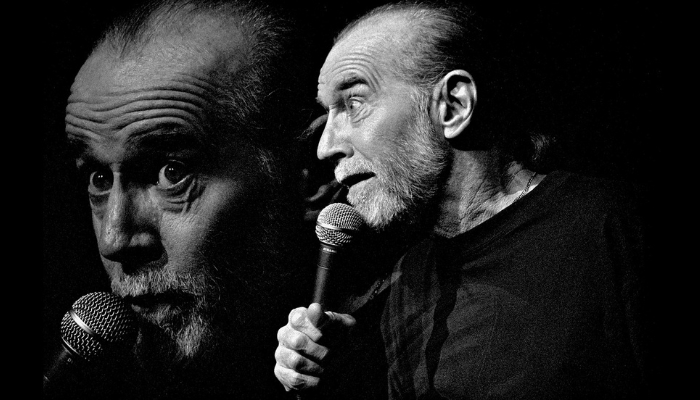

The AI doppelganger case has been resolved by the estate of George Carlin

3 min read

A lawsuit claimed that Carlin’s copyright had been violated by the Dudesy podcast, calling it a “casual theft of great American artist’s work.”

The lawsuit against a comedy podcast that used artificial intelligence to replicate George Carlin’s voice was settled by the estate of the late comedian. One of the first cases in the US to tackle the legality of deepfakes that imitate celebrities was this one.

The producers of the Dudesy podcast, writer Chad Kultgen and comic Will Sasso, committed to never using Carlin’s voice, likeness, or image again and to removing all of the show’s episodes off the internet. Sasso’s spokesperson, Danielle Del, declined to comment.

“I am pleased that this matter was resolved quickly and amicably, and I am grateful that the defendants acted responsibly by swiftly removing the video they made,” said Kelly Carlin, the comedian’s daughter.

Carlin’s estate filed the lawsuit in January after the Dudesy podcast, which incorporates AI into its comedy routines, uploaded an hourlong special on YouTube titled “George Carlin: I’m Glad I’m Dead.” The estate’s suit alleged violations of Carlin’s rights of publicity and copyright, describing it as “a casual theft of a great American artist’s work.”

The AI character from the podcast, “Dudesy,” gave a brief introduction to the programme, saying it had studied Carlin’s work and created a stand-up routine in his vein. But Del, a spokesman for Sasso, told the New York Times following the lawsuit that AI did not create the imaginary character Dudesy. Rather, Kultgen composed the whole fictitious Carlin special without drawing any inspiration from Carlin’s earlier work. It’s still unknown which elements of the fictitious Carlin set were produced by AI because the case did not move on to the discovery stage.

Kelly Carlin expressed regret over the incident and hopes it serves as a cautionary tale about the risks of AI technologies. She emphasized the importance of implementing appropriate safeguards not only for artists and creatives but for everyone.

Despite the podcast not using Carlin’s comedy to train an AI, an attorney for the estate argued that using the technology to create an impersonation of him still violated Carlin’s rights. They also deemed the disclaimer before the special insufficient. They raised concerns that clips from the special could have been taken out of context and falsely attributed to Carlin, who passed away in 2008.

Partner at Boies, Schiller, Flexner and lawyer for Carlin’s estate Josh Schiller said, “These kinds of fake videos present a real risk of harm because someone could easily clip a segment and share it or post it on Twitter.” “Someone might be misled into thinking they’re listening to the actual George Carlin, especially if they’re unfamiliar with his voice and unaware of his passing.”

The settlement comes at a sensitive time for artificial intelligence’s role in the entertainment sector. Over the past 18 months, the number of easily available generative AI tools has expanded, which has made creators more concerned about unlicensed copying of artists, living or dead. Limits on malevolent or non-consensual uses of AI technology are being considered by governments and AI businesses in response to recent cases of deepfakes involving celebrities such as Taylor Swift.

In an open letter earlier this week, over 200 musicians urged developers and tech companies to stop using AI technologies that could violate their rights and misappropriate their likenesses. At the same time, a number of states have proposed laws pertaining to deepfake technology. For instance, a legislation recently established in Tennessee forbids using an artist’s voice without the artist’s permission.

The swift resolution of the case underscores the potential for future legal disputes over whether AI-generated imitations could be deemed parodies protected under fair use. While shows like Saturday Night Live have historically been allowed to impersonate public figures on these grounds, there have been few significant legal challenges regarding generative AI tools creating similar impressions—a situation that Schiller contends is fundamentally distinct from human impersonation.

“There’s a substantial difference between using an AI tool to impersonate someone, making it seem authentic, and a person putting on a gray wig and a black leather jacket,” Schiller explained. “You know that person isn’t George Carlin.”